The Wyandot People

The Wyandot (or Wandat) people came to Kansas in 1843. They were the last Native American tribe removed under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The first known Wyandot villages were located near Montreal, Canada. By the 18th century, war with the Iroquois forced the tribe to migrate to the Ohio Valley region, where they eventually secured land in Upper Sandusky, Ohio. As the area became increasingly attractive to white settlers, the Wyandot came under pressure to cede their lands to the federal government. They signed a treaty in 1842 and headed west to Kansas, where they were promised 148,000 acres. No land was available when they arrived, and they purchased 44,000 acres from the Delaware tribe. In 1867, the Wyandot were removed again, this time to Oklahoma, where the Wyandotte Nation continues to live today. The Wyandot who remained in Kansas now make up the Wyandot Nation of Kansas. Along with the Huron Wendat of Wendake (Quebec, Canada) and the Wyandot of Anderdon Nation (Michigan), the four tribes are the Wendat Confederacy.

Wyandot Migration Trail

To honor the history of the Wyandot tribe, the Kansas City, Kansas Public Library has shared their migration story on an interactive map. The first documented contact with the tribe was in 1535, in present-day Montreal. This map shows the significant points of history from that event onward, highlighting the places the Wyandot tribe moved to make a home. Subsequently, they were forced to move multiple times, leaving family members, history, and culture behind.

We hope that by honoring the history of the migration of the Wyandot people will help educate others about the past of our home, allowing us all to better understand and value what brought us to our present. This story map is our pursuit to provide you with insight into the history and culture of an underrepresented indigenous people of America.

Conley Sisters

About the Conley Sisters

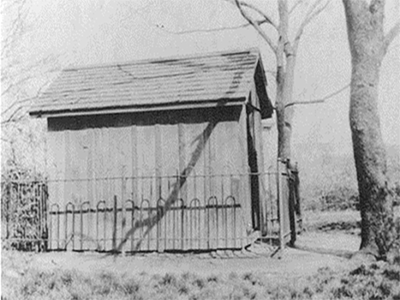

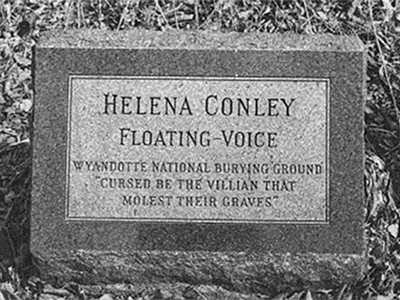

The Conley Sisters served as the champions of the Huron Cemetery. The sisters, Lyda, Helena, and Ida, came to the defense of the cemetery when Congress proposed selling the land. To defend the cemetery, the Conley sisters erected a small, fortified shed on the grounds and, through their efforts, succeeded in saving the historic location. Lyda defended the cemetery before the United States Supreme Court. This action made her the first woman of Native American ancestry to appear before the high court and argue a case. Although she lost, Lyda and her sisters gained support for their cause, and the Huron Cemetery was not sold. Decades after the Conley sisters died, the federal government approved and improved the cemetery through work with the City of Kansas City and Urban Renewal plans.

The Huron Cemetery

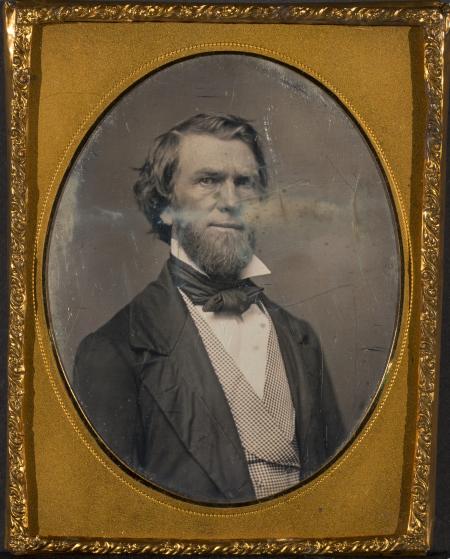

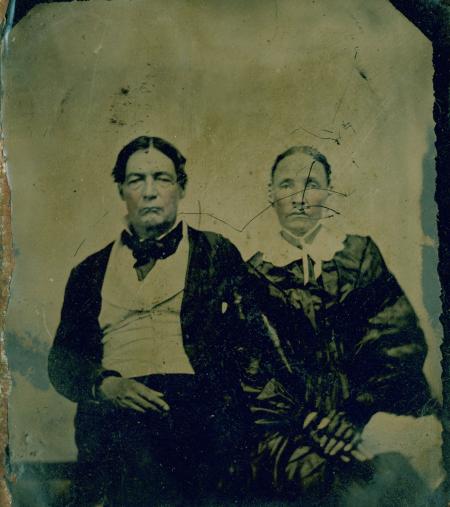

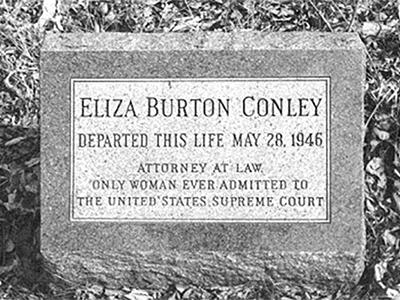

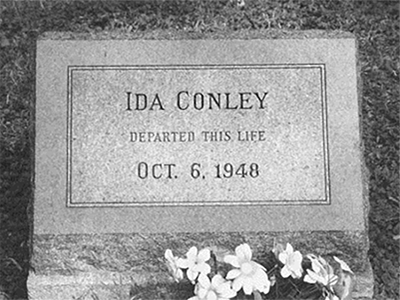

The following images relate to the Conley Sisters.

Conley Sisters Articles & Video

| Article Title | Date Published | Description |

|---|---|---|

| N/A | Introduction, overview, and suggested reading for those researching the Conley Sisters. | |

| 1910 | Lyda Conley's argument presented to the Supreme Court of the United States. | |

| 1910 | Interview with Lyda Conley regarding her work and the lawsuit over Huron Cemetery. | |

| 1910 | The Supreme Court decided on the Conley v Ballinger on Jan. 31, 1910 with its opinion delivered by Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes, Jr. Conley lost her case, but gained support for her cause. The Huron Cemetery was not sold and no bodies were disrupted. | |

| June 7, 1946 and May 17, 1959 | Two articles from the Kansas City Times that focus on the Conley sisters and their defense of the Huron Cemetery. | |

| May 28, 1946 | Obituary notice and article about Lyda Conley. | |

| Oct. 6, 1948 | Obituary notice and article about Ida Conley. | |

| Sept. 16, 1958 | Obituary notice and article about Helena "Lena" Conley. | |

| Sept. 19, 1858 | Story about the funeral and burial services for Helena Conley. | |

| Feb. 29, 1976 | The federal government approved city and Urban Renewal plans for Huron Cemetery improvements. Article interviews Conley sister friend to gain perspective on what their reaction would be. |

Huron Cemetery Segment

KTWU's Sunflower Journeys featured Huron Cemetery in a segment, which aired on Dec. 12, 2017. The segment begins about 10 minutes into the video.

Daguerreotypes

Developed in France in 1839 by Louis Daguerre, the daguerreotype was the first commercially successful photographic medium. To create the image, a daguerreotypist would polish a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish, treat it with fumes that made its surface light sensitive, then expose it in a camera for a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or several minutes in low light. The resulting latent image was developed by fuming it with mercury vapor, removing its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment. It was then rinsed and dried before sealing the fragile plate behind glass in a protective enclosure. The image is on a mirror-like silver surface and appears either positive or negative, depending on the viewing angle. By 1860, daguerreotypes were mainly replaced by less expensive and simpler photographic processes, such as ambrotypes, tintypes, and albumen prints.

Learn more from the Library of Congress Daguerreotype Medium

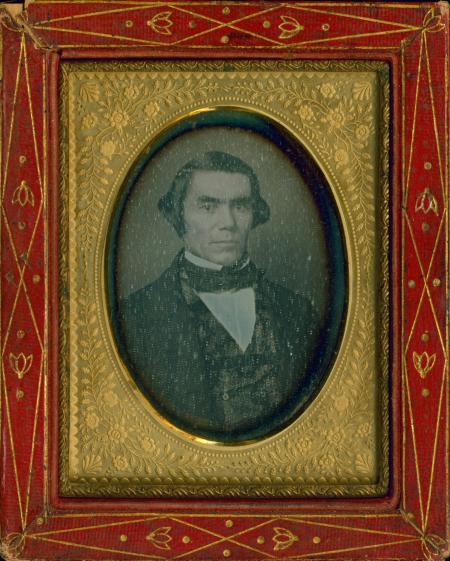

Abelard Guthrie Portrait

The daguerreotype of Abelard Guthrie is a part of the William Connelley Collection of Wyandot history, held in the Kansas Room. It is one of only a few known images of Guthrie, the husband of Quindaro Brown, a Wyandot woman and daughter of Chief Adam Brown, and one of the founders of the Quindaro Township. Over the years, the image cover glass was damaged, and the image became severely tarnished. A Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area grant funded the conservation treatment, which will preserve the image for years to come. The Guthrie daguerreotype was a part of an exhibit at the Main Library of Wyandot portraits.